Oil and Gas Traps

All oil and gas deposits are found in structural or stratigraphic traps. You may have heard that oil is found underground in “pools,” “lakes,” or “rivers.” Maybe someone told you there was a “sea” or “ocean” of oil underground. This is all completely wrong, so don’t believe everything you hear.

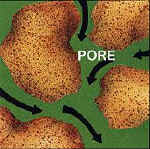

Oil Moving Through Pore Space In Sandstone

Most oil and gas deposits are found in sandstones and coarse-grained limestones. A piece of sandstone or limestone is very much like a hard sponge, full of holes, just not compressible like a sponge. These holes, or pores, can contain water or oil or gas, and the rock will be saturated with one or all of them. The holes are much tinier than sponge holes, but they are still holes, and they are called porosity.

The oil and gas become trapped in these holes, stays there, for millions of years, until petroleum geologists come to find it and extract it.

When you hold a piece of sandstone containing oil in your hand, the rock may look and smell oily, but the oil usually won’t run out, and you can’t squeeze sandstone like a sponge! The oil is trapped inside the rock’s porosity.

Oil Formation and Oil Movement

The very fine-grained shale we talked about previously is one of the most common sedimentary rocks on earth. In many places, thousands upon thousands of feet of shale are stacked up like the pages in a book, deep underground. It is not unusual to have layers in the earth’s crust made up mostly of shale that are 4 miles thick. These shales were usually deposited in quiet ocean waters over millions of years time.

During much of the earth’s history, the land areas we now know as continents were covered with water. This situation allowed tremendous piles of sediment to cover huge areas. The oceans may have left the land we now live on, but the great deposits of shale and sandstone remain deep underground….right under our feet!

The Tiny Gigantic Kingdom

In the deep ocean, far from land, about the only sediment deposited is the fine-grained clastic rock known as shale. But what about the oil and gas? For the answer, we need to move to the ancient oceans that once covered almost all of the earth.

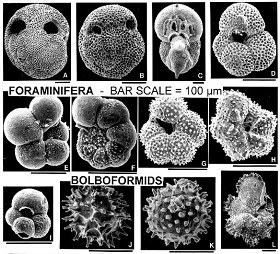

Tiny Microfossils Make Up the Sea-Floor Ooze

A lot of other material is deposited along with the clay or mud-sized sediments. We often think of sharks and whales as being the kings of the deep oceans. Actually, there are other animals that have established giant kingdoms in the sea…the largest and most impressive kingdoms of all! These animals are the various kinds of microscopic creatures….both plant and animal. Most of them would fit on the head of a pin. They are tiny, but there are uncountable trillions of them. When these creatures die, they sink to the bottom and become part of the sediments there that will eventually turn into shale.

The animals die by the trillions and rain down on the ocean floor all the time. And since the beginning of life on earth, they have been living their lives in the ocean, dying, sinking to the bottom, and becoming part of the once-living matter that is a good part of most shale rocks.

It is the trillions of tiny animals that make up most of the gunk (the scientific name for this gunk is “ooze”) deposited on the ocean floor. It’s a very fine-grained goop containing a lot of organic material mixed with the clay-sized particles that form shale. It is called organic-rich shale.

Later, when thousands of feet of organic-rich shales have piled up over millions of years, and the dead animal bodies are buried deeply (more than two miles down), an amazing thing happens. The heat from deep inside the earth “cooks” the animals, turning their bodies into what we call hydrocarbons……oil and natural gas.

At first, the oil and gas only exist between the shale particles as extremely tiny blobs, left over from the decay of the tiny animals. Then, the  intense pressure of the earth squeezes the oil and gas out of the shale, and the oil and gas fluids gather together in a porous layer and may move sideways many miles. On their way, they may meet up with other traveling oil or gas fluids.

intense pressure of the earth squeezes the oil and gas out of the shale, and the oil and gas fluids gather together in a porous layer and may move sideways many miles. On their way, they may meet up with other traveling oil or gas fluids.

Finally, the oil and gas may become “trapped” in a rock formation like sandstone or limestone….a hydrocarbon trap. The oil and gas stay there, usually under tremendous pressure, until the petroleum geologist comes looking for it. Without a trap, the geologist has no place to drill. All oil and gas deposits are held in some sort of trap.

The Two Types of Traps

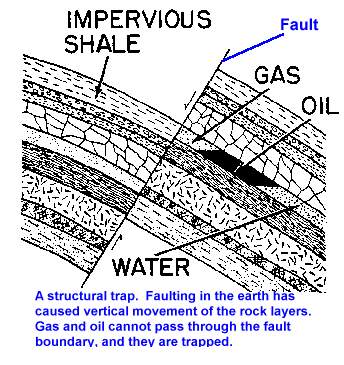

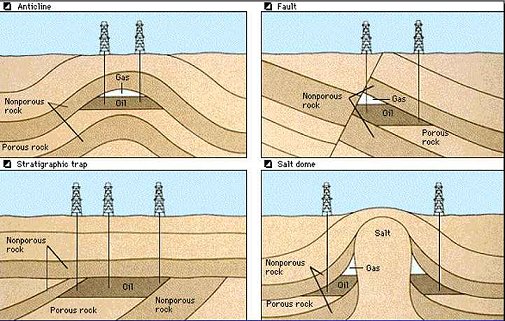

Structural Traps

These traps hold oil and gas because the earth has been bent and deformed in some way. The trap may be a simple dome (or big bump), just a “crease” in the rocks, or it may be a more complex fault  trap like the one shown at the right. All pore spaces in the rocks are filled with fluid, either water, gas, or oil. Gas, being the lightest, moves to the top. Oil locates right beneath the gas, and water stays lower.

trap like the one shown at the right. All pore spaces in the rocks are filled with fluid, either water, gas, or oil. Gas, being the lightest, moves to the top. Oil locates right beneath the gas, and water stays lower.

Once the oil and gas reach an impenetrable layer, a layer that is very dense or non-permeable, the movement stops. The impenetrable layer is called a “cap rock.”

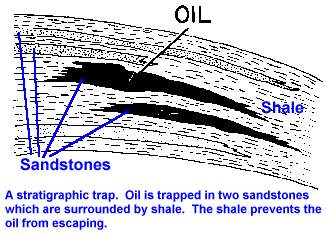

Stratigraphic Traps

Stratigraphic traps are depositional in nature. This means they are formed in place, often by a body of porous sandstone or limestone becoming enclosed in shale. The shale keeps the oil and gas from  escaping the trap, as it is generally very difficult for fluids (either oil or gas) to migrate through shales. In essence, this kind of stratigraphic trap is surrounded by “cap rock.”

escaping the trap, as it is generally very difficult for fluids (either oil or gas) to migrate through shales. In essence, this kind of stratigraphic trap is surrounded by “cap rock.”

Here are four traps. The anticline is a structural type of trap, as is the fault trap and the salt dome trap.

Four Types Of Structural and Stratigraphic Traps

The stratigraphic trap shown at the lower left is a cool one. It was formed when rock layers at the bottom were tilted, then eroded flat. Then more layers were formed horizontally on top of the tilted ones. The oil moved up through the tilted porous rock and was trapped underneath the horizontal, nonporous (cap) rocks.

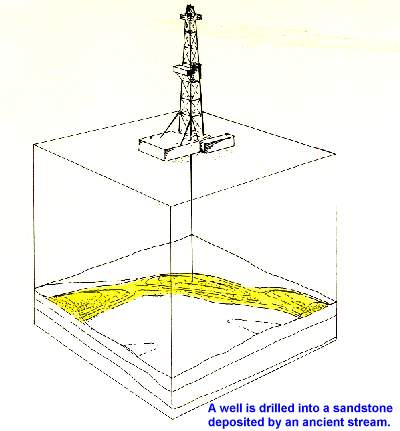

Another Stratigraphic Trap

This hole has been drilled into a sandstone that was deposited in a stream bed. This type of sandstone follows a winding path, and can be very hard to hit with a drill bit! The plus is that old  stream beds make excellent traps and reservoir rock, and some of these types of sand bodies are tens of miles long!

stream beds make excellent traps and reservoir rock, and some of these types of sand bodies are tens of miles long!

This type of sandstone is usually enclosed in shale, making this a stratigraphic trap.

Just because you drill for oil or gas does not mean that you will find it! Oil and gas reservoirs all have edges. If you drill past the edge, you will miss it ! This might explain why your neighbor has a well on his land, and you do not!

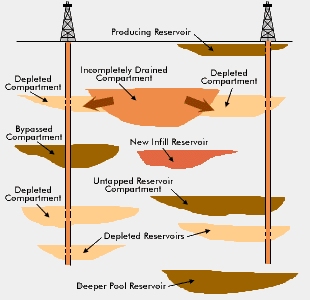

Stratigraphic Problems When Drilling

When you drill, you may find a producing reservoir very near the surface. But many other things can happen:

You might drill into a reservoir that has been depleted (all the oil and gas removed) by another well (diagram at left). There may be a new infill reservoir between two wells that could be developed with a third well. Or  one that was incompletely drained. Maybe if you drill a little deeper you might hit a deeper pool reservoir! You might be able to back up and produce a bypassed compartment. The petroleum geologist has to think of all these things when planning a new well!

one that was incompletely drained. Maybe if you drill a little deeper you might hit a deeper pool reservoir! You might be able to back up and produce a bypassed compartment. The petroleum geologist has to think of all these things when planning a new well!

Structural Problems When Drilling

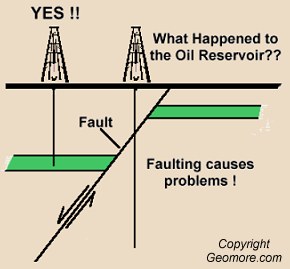

Finally, structures in the earth can give the PG many challenges. Look at this diagram. Imagine you first drilled the hole on the left into the green layer which represents a nice oil and  gas-bearing rock. YES! You have a great well, producing lots of oil and gas!

gas-bearing rock. YES! You have a great well, producing lots of oil and gas!

Then you drilled your second hole to the east (right) of the first one. What happened to that hole? (answer below)

Answer: The oil reservoir has been split in two by the fault, which is nothing but a place in the earth where rock layers break in two. The arrows on the diagram show that the rocks moved DOWN on the LEFT side of the fault and UP on the RIGHT side of the fault. This created a GAP in the oil field……right where you drilled your second hole! Incredibly bad luck! Or, bad seismic! Your second hole is a DRY HOLE.

Some diagrams from “A Primer of Oil and Gas Production” and “Pennsylvanian Sandstones of the Mid-Continent”